About

Shruti Gandhi, GP wears multiple hats as a GP and LP. She is a commissioner at San Francisco Employees’ Retirement System. As an engineer, is highly technical and has institutional investing experience prior to Array Ventures at True Ventures and Samsung Next Fund.

Shruti has invested in over 60 companies in their first rounds which are now worth billions. Many have been acquired by Apple, Paypal, ServiceNow, Amazon, and others. She was on Techcrunch 10 VCs that founders like list alongside investors from Greylock and First Round.

Summary

How do you make it in a new country when you don’t know the first thing about surviving, let alone thriving, when your peers are already miles ahead of you. How do you reverse-engineer problems so you can break through brick walls to accomplish what you want? And how do you do all this in a completely homogenous , male dominated field?

In today’s episode, entrepreneur and B2B venture capitalist Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi talks about finding your place in a tough ecosystem, succeeding as an invisible minority, staying motivated and laser focused regardless of setbacks, the secrets to founding a venture backable firm and more.

Episode highlights

- How to get started in a new country when you know nothing and have nothing

- Challenges of getting funded as a female founder in tech

- How to leverage what you have to get what you want

- The one trick to figuring out how to achieve any goal

- How to know if the business you’re founding is backable

- The three building blocks of a fundable venture

- How to speak from a place of power when pitching

- The surprising truth about advice, and why most women founders miss it

- The unique challenges of being a South Asian founder in tech

- Smart ways tor reduce social risks as a single female founder

- How to maximize your chances of being a successful founder

Links & Resources

Array VC – Enterprise deep tech vc firm that Shruti founded

Interview transcript:

Shubha Chakravarthy: Welcome to our podcast. We are delighted to have you here today!

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: Thank you so much for having me! I’m so excited.

Shubha Chakravarthy: So, tell us about Array, your rare breed of a venture capitalist. Tell us what Array does and how you got into it.

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: Array Ventures invests in enterprise pre-seed stage companies. We are the first check usually, as early as the company’s formation and we like leading those rounds and we can follow if necessary but our average check size is a million and a half to 2 million.

We like to help our companies get from what we call the 0-1-10. So, from when they are starting their formation at 2 million ARR to setting them up for 10 million ARR. As I said, it is an enterprise fund focused on infrastructure, cloud security data, all the good backend things. Sometimes, we also do an application layer if we have a strong conviction around those front-end application focus areas as well.

So, anything B2B is fair game, I would say.

Shubha Chakravarthy: Looking at your background and rewinding a bit, I know you came from India and I read a story about how you had a really interesting start. Can you tell us a little bit about that journey and what got you into tech?

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: I came here with nothing. I’d worked really hard in India to get good grades, like all our parents pushed us to do. Then I came here and I had literally no idea about getting into college because I was an immigrant. I came here right after my high school in India, after 12th grade. When I got here, we didn’t know the process of getting into college which required SAT scores and all. I had done no prep and I didn’t understand which college applications I should look at.

I kind of had to figure out my way. I had never even thought about what I was going to study. I had to pick that at that time. At first I thought that since my dad was in the architecture-construction world, I would be an architect. I also wanted to be a fashion designer, like every person at that age and then I quickly realized — with a lot of my family telling me that you need to do something meaningful that makes money that you have to make money to make sure that you are able to support your family and my brother was going come to the US a few years later so I had to think about that.

So, I was like, “Okay, what makes money at this time? Alright — computers, let’s study that.” In the meantime, I taught myself how to code and I also started working at this computing lab at a school in my neighborhood. I convinced that school to accept me without SAT scores and I graduated in three years. In the meantime, I also started working at IBM, which was in the same town in Poughkeepsie, New York.

I started doing all of that at the same time. I had a job before I graduated and I graduated in three years. So, it was one of those things where once there was a mission in place, which was, “I have to make money”, I just kind of oriented myself around it. I’m pretty good at that. I’m pretty good at figuring out the task at hand and I think most people are too. I think once you are guided to make an end goal happen, which was, “You need X amount of money and this is the best way to make money right now.” You can do it then.

I’m not sure if that was the best way or not. I could have started a company. I could have done so many other things, but I also didn’t have any money. So, I would say that’s how I got started in the tech world as your question is and then to continue on, I worked in it for just 10 years because then I realized that I didn’t love what I was doing.

I was doing backend programming and assembly and basic stuff and I kind of was like, “I don’t like it. I’m going to move on from here to maybe the application layer. I don’t know what that really means, but I’m going to keep doing that.” So, I ended up working in different business departments at IBM and then I rose in the ranks, figuring out one step at a time, basically.

I worked in the chairman’s office at one point. The chairman at the time was Sam Palmisano. To continue and to explain how that brought me where I am today, it was there that I learned about venture capital. I had no idea what that was before. I was just telling someone that I had to Google what it meant.

As I was figuring that out, I was like, “Oh, this is a fascinating industry. I want to start a company”, because I come from an entrepreneurial family and I knew that I just needed some money for venture business. I learned, “Okay, maybe you don’t need that much money to start something. So, let’s figure it out.”

I started a company but I still didn’t really know what venture capital was. I didn’t really know how to raise money. I was not in the Bay Area. I was in Chicago and New York for over 10 years. I didn’t really have connections, I just had a corporate job and I’d never really been exposed to much. So I kind of figured out, “Okay. I should learn venture capital”, without knowing how hard or easy it was and then honestly I just got into venture capital and I have been in VC for 10 years now.

The reason I got into venture capital was because I couldn’t figure out how to raise money. That’s when I got into VC to learn how to raise money and we learned the venture business and how VC scale business works and then once I got into VC, I was like, “All right, I think I have enough experience — like four or five years. Let’s go start a fund. Well, let’s go start a company!” It ended up becoming a fund and now I’m six years in. I have a fund. I cut out a lot of big pieces just to lay down the land here.

Shubha Chakravarthy: That is an excellent introduction! You talked a little bit about not having the money and going down the VC route versus the founder route. Were there other factors that drove that decision for you to become a venture capitalist versus becoming a founder?

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: I was a founder but I couldn’t raise money, so that’s when I decided I wanted to learn the venture business and I was like, “I’m technical and my co-founder’s technical. We are building and working on a decent problem. What’s the problem here?”

There were so many problems around at that time that I’ve learned about over the years, but the goal was to reverse engineer venture. Once I figured that out, then my goal was to be cool enough to go and raise money in like a few weeks and close it, the round and stuff. So, that was the goal.

The goal was if I master venture I will understand the lay of the land and I will understand what makes it a venture pack business versus just a bootstrap slow growth kind of capital-efficient business. So, that was the goal and that’s how I got into venture.

Shubha Chakravarthy: Ventures are notoriously hard to raise money for, especially if you are a first time venture capitalist. The stats for venture funds themselves aren’t supremely encouraging. What was the secret to cracking the code? How did you get a venture and how did you start raising funds for your venture fund?

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: Honestly, I got lucky! I didn’t know about all the hard things. Once I figured out I wanted this, I just made it a goal. Recently someone described me as, “Someone who can run through a brick wall.” I’d never thought of myself in that way, but I think am like that.

I think once there is a challenge in front of me and it is reasonable enough, then I go for it — I mean I’m not going be the best Olympic runner, I know my strengths and weaknesses — but in terms of the knowledge economy, not physical limits and stuff. I know what I want to accomplish and I also am very much structured in terms of figuring out what my strengths and weaknesses are.

So, I decided venture was something I wanted to learn more about and do and then once I started looking for a job, I realized how hard it was to actually to do it. But I got lucky. I said, “What are my strengths and what kind of networks can I leverage to make that happen?” I got into the University of Chicago – Business School and that’s when I was also starting the company. So, what I said was, “I’m going to use the networks to get into venture capital.”

It was still hard and I was probably one of the only people at that time and that year that got into venture while in business school. I think I just leveraged all the networks I had when I was in Chicago. I made numerous trips on my own dime and crashed on many couches.

I think it would require a different game now, 10 plus years later. But I did what I needed to at that time to at least get meetings with people and one by one explore different paths and build relationships. I would even do work for free. Often I did a couple of internships at the time, working for VC funds for free and things like that.

You just had to play one step at a time and starting my fund was also a moment of luck. I left my firm to go start a company. I was working for other firms and the founders I’d worked with over four or five years, I’d been lucky to get some exits and stuff at the time already. They were not gigantic exits, but they were exits to companies like Apple and Samsung. So, those founders said, “Hey, if you’re doing something we would love to back you.”

Again, it all shows that people believed in me, I guess. So, that’s when I went and took one step to two steps to the next step and just kind of ended up starting a small firm, again, leveraging my network. It is all about luck, married with me pushing through and making that an opportunity I wanted to pursue, I guess.

Shubha Chakravarthy: I’m going to change gears slightly and talk about the other side, which is the companies you invest in, particularly from the point of view of under-resourced women entrepreneurs. For under-resourced women entrepreneurs, what would you say are the most critical things for them to be able to get successfully funded by venture capitalists?

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: Ah, such a tough question. I can’t be the one to tell you that there’s a magic bullet, right? I can only talk about my experience, which is what I did, which says that you always have to stay one step ahead. I always read a lot about what someone did and I’d take that on as my challenge, “Oh, someone raised such and such kind of capital?” and I think about it and I’m like, “Can I accomplish that? I don’t know. What is lacking in me?”

I’m not comparing but in a way I am just trying to figure out where I stand because in some ways it is written about many times, which is like, “You need to go to a certain kind of school. You need to do certain stuff. You need to look a certain way.” I don’t have those. So what do I need to do?

I always talk about how I can differentiate myself in the crowd and then once I do that, I talk about what else can I do to differentiate further. The other way to look at it is, “What are my strengths that others don’t have?”

So, in my world it was very straightforward. I was a nerd that understood enterprise and data pretty well and I’m a woman, which is another thing. Very few people generally understand deep tech data but on top of that very few women are on the spectrum of investing. I am probably one of the few handful of women at this stage, now the pre-seed stage, as in the first check stage, and that is my strength.

Anyway, I kind of narrowed that down and said that if that differentiates me then that simply differentiates me and I love that but again, I’m not gonna do something just because it differentiates me. I wanna also love it because I’m gonna be doing for the next few decades.

So now, if you are starting a company then the thing I would say, as an underrepresented founder is first, “What is your strength? Have you worked in this industry before?” If you haven’t then I would not do something, especially the first time around, in that category in that industry. If you are gonna go start something in whatever industry you are doing and if you have not worked in that space then you won’t have the confidence to solve problems in that space and that goes for anyone, not just underrepresented founders.

The second thing I’d do is ask myself if I have a differentiated perspective in that category. If I don’t, then again, what am I gonna go out and say? “I wanna start a company next”, but why? What is your differentiated view here?

Third, build a solid team. Going at it alone or going at it with a team that cannot build a product is really hard. That’s the hardest thing to tell you as well because it is just really hard to say, “Find a technical co-founder or something”, right?

But at the end of the day, if you don’t have money and if you are going to want to build a product, then the cheapest way to build it is in house — versus hiring a firm. Again, at the end of the day, VCs don’t want to back founders that don’t know much about this space and on top of that — have a firm that they are hiring to build the product.

So, I know it is disappointing to hear all this but I think you have to position yourself from a place of strength to be able to raise capital. That is what good teams need, underrepresented or not, to raise capital. So I would strengthen your base here, before you go out to raise capital.

Shubha Chakravarthy: I want to touch on the second point you made, which is about having a differentiated view of the “Why”. Can you give any examples either from your portfolio companies or the pitches you’ve seen, which are good examples of that and things that may not be good examples of what a differentiated view is?

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: It’s straightforward, even without giving examples. It is more like — “I worked in this industry for five years, two years, or a few years.”

We have this thesis called “Agitated workforce” and I did this at my previous company. It was very frustrating but I wanted to solve this “X problem” that I knew really well and when I went to pitch that as a product in our company, I couldn’t get funding. I got upset. I got agitated because this needs to be solved and it makes me less efficient. So, smart people don’t wanna waste time. That’s a fundamental thing that I back. So, when they want to go solve something they go talk to their friends and their friends say, if you build this, I’ll buy it.

Basically that is what convinced them to go build this product outside of their company because it was so hard for them to do it in their own company and their friends or others outside gave them conviction to do so. That is what it takes. You need to have done the work beforehand to go validate this with, I would say like at least 40-50 plus customers.

So, one of my recent companies, I can’t talk about it yet, but they said, “We pulled this multiple times in our own companies, in companies we worked for before, right? Again, now our own founder of those companies has convinced us to go leave our jobs and go start that as a new company — and then by the way, that founder is backing us as well.”

When you pitch something like that, it is from a place of power versus a place of defense, which says, “I think we should work on this. I don’t know if it’s gonna work and I have no experience.” That’s a bad story, right ?

Shubha Chakravarthy: Thanks for explaining that further. I’m going to take a slight detour also on the question of pitching, especially for women founders. What is your experience from the other side as one of the people who are funding in terms of women and their grasp of the financial fundamentals of their business, especially with regard to under-resourced women entrepreneurs?

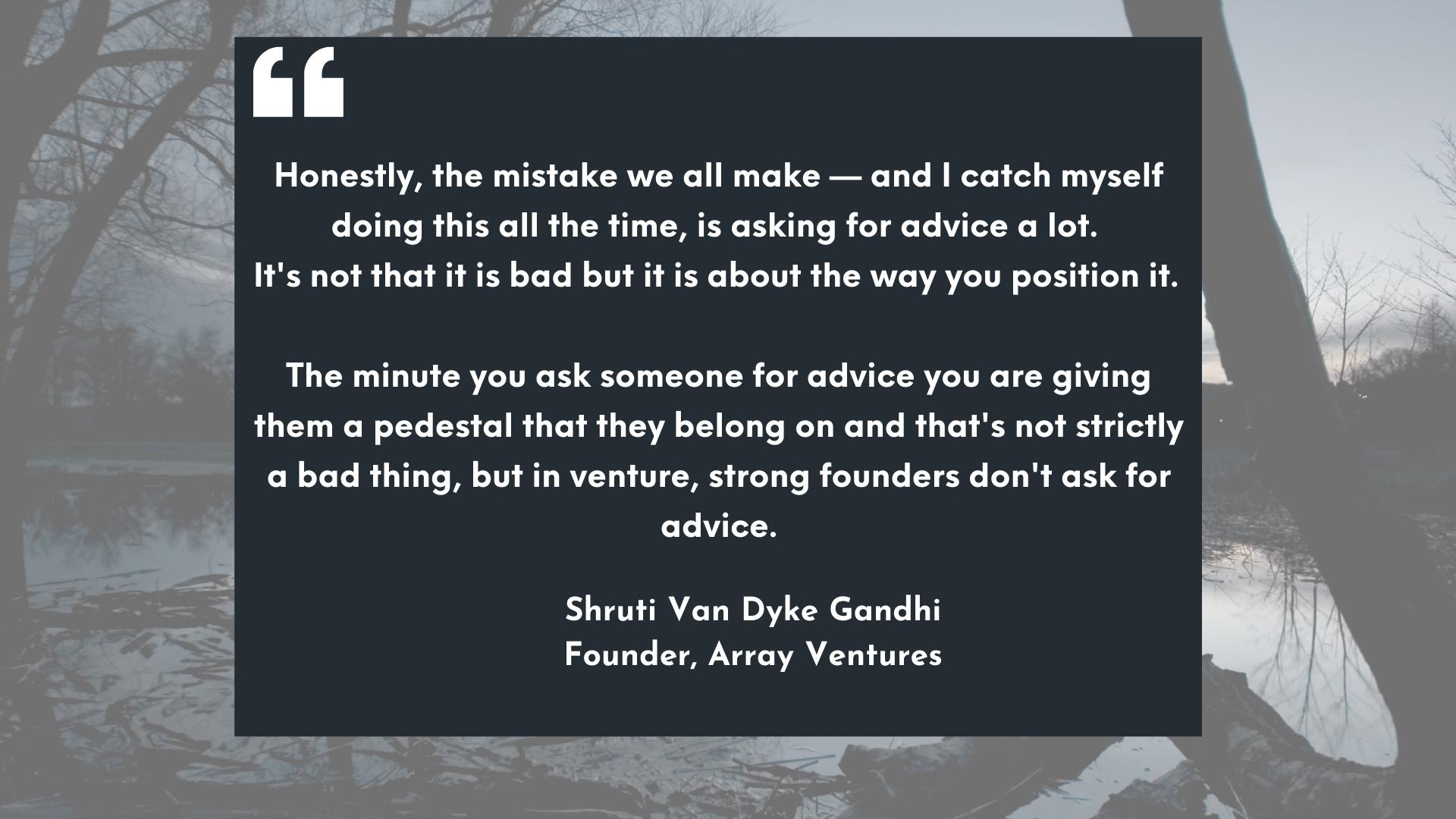

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: Honestly, the mistake we all make — and I catch myself doing this all the time, is asking for advice a lot. It’s not that it is bad but it is about the way you position it. The minute you ask someone for advice you are giving them a pedestal that they belong on and that’s not strictly a bad thing, but in venture, strong founders don’t ask for advice.

The difference is asking for advice in the dark versus asking for advice that is in context.

When I say there is a way to do it, you can say, “I’m doing this and you”, the VC person X or Y, “have seen this industry. Here is our approach. Do you wanna invest?” The VC then starts saying, “Well, I’m experienced, I don’t see it working.” Then you can say, “Okay, why not?” Or “Here’s why we think it would work.”

It’s a very straightforward path to take versus , “Oh, you are so amazing. You are so great. Can you give me advice?” That opens such a can of worms in a person’s head and that undermines that person already, which is something you don’t want. So I think, the perspective is — don’t go asking for advice. Come with a solution and say, “Do you have an opinion or do you wanna react on this?” That is a better way to position it.

There are so many others but this is just one thing that irks me when founders do it, especially under-represented founders. I sometimes do it myself. To catch yourself, you have to do a lot of homework beforehand before you do that.

Shubha Chakravarthy: Are there others that particularly irk you in terms of under-resourced founders that you think would be helpful for us to know of?

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: This is the best one. I think if you just take care of the fundamentals here with what I’m saying, you will come across as more confident and strong but very often we don’t because we lack that legwork.

Shubha Chakravarthy: So, legwork is key. Homework is key. Knowing your subject matter is key. Knowing your thesis and knowing why your business is — is key. This is what I’m hearing.

One other thing that I was very interested in is when a potential founder comes and presents their thesis or company and clearly there are some financials that they have to talk about. What is your experience seeing women founders present the financial fundamentals and their business as opposed to male founders that you think would be good for us to hear?

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: Honestly, finance is the last thing I look at — at this stage. I know it’s a funny thing but I am a pre-seed investor and I believe in someone wanting to solve this for 10 years before I’m looking into the finances because even though finance and fundamentals are important, especially now when you want to know when your first customer is coming in and how you are getting to a hundred million — all those basics are important, but that’s not why I invest. I invest in why someone wants to solve a problem in a very meaningful and differentiated way and then I am the reason that can help them think about finances more.

Shubha Chakravarthy: In terms of enterprise tech, tech founders, or the tech space in general, are there things that you would suggest or that you are seeing in terms of trends of under-resourced women?

What are the things that are making you feel good about this positive developments versus what are some of the areas where there might be concerns or potential opportunities for women to do a better job to succeed in general as well as be successful in getting funded?

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: It is unfortunate. The numbers in women founders being funded are so low and I really wanted to do something there — a third of our founders are women by the way. Those are much higher numbers than the industry but we are restricted since I am a B2B investor. So for me, if women are not starting B2B companies then the pool is small and then I have to really work hard to then find the best founders from that small pool.

I would say that if you are going to start a company, just be very cautious of these three things.

One — start something that you know well, for your first business. If you make money the first time around then the second time around no one will be questioning you.

Solve something that is meaningful and that can also generate revenue right away. A lot of the businesses that founders pitch end up being ones that make money in year two or something. So, end up starting businesses that don’t need that much cash and you can start generating revenue early on. At the end of the day VC’s like traction, it may not be getting you millions of dollars yet, but any dollar you are able to get is valuable.

Start businesses that are not in a crowded space. So do your legwork. it is kind of hard to raise money in marketing, eCommerce, MarTech, sales, tech, as these are areas that are well funded at this time, unless there is something unique that comes my way from some real experience found in the category.

So, if you don’t have experience, don’t start companies in that category.

Shubha Chakravarthy: Switching gears slightly, you come from a South-Asian background which I share with you, and there are some cultural aspects related to that. Can you talk about if and how your heritage has impacted your journey and what learnings you’ve gotten from them that you think might be helpful to others?

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: On the positive side, it shows that I’m one of the few South-Asian investors in deep tech or at least in the enterprise kind of stuff and yes, it has made me strong because it was a hard journey.

To be honest, there is a lot of support for South Asian men in our industry or I think or in our world and then the numbers are so unfortunately skewed. So, when you talk about the underrepresented, South-Asians don’t count and South-Asian women get affected for that reason, because I’ve heard from investors so many times to my face that, “Oh, I care about people of color, but I don’t care about Asians – South Asian folks. You are not a minority.”

That is unfortunate because we are. The amount of South-Asians generally in this country is less than 3% or 4% but people like to believe, “Oh, you’ve been able to get success on your own. You are not gonna be qualified for these pools of capital that is allocated for that.”

Unfortunately, out of all South-Asians who are CEOs out there, there are maybe two or three that are South-Asian women and they don’t even get talked about as much. In venture, when I started this journey, it was unfortunate as I was not in the age bucket and I was not in the the demographic or everything else people might be looking for.

Our own community is not helpful to us as well. We, as women, don’t know who to reach out to and all the the men like being “Bro-y” and helping each other out, even in the “IIT network” and everything, how many are women? It is unfortunate how hard they have to work as well.

So, it is unfortunate in many ways, but again, once I had decided I’m gonna make it on my own and I did. So, the brick wall perspective helps again. I think that’s what I did. I wanted to be on my path and I found my own track. It may or may not be South-Asian. There are lot of amazing men who have helped me along the way, South-Asian men as well, but there are many who have not, who could have easily, just because they didn’t see it in me.

To be honest, I was the underrepresented founder who made all the same mistakes that others are making. I asked for advice and people would look at me and say, “You don’t have venture experience. I’m not gonna back you.” The advice I’m giving is from the fact that I’ve experienced all this on my own and I think that for me, it is one of those things where I’m doing this job because my life is my message.

As Gandhi says — and my last name’s Gandhi as well, I’m doing this because I want to leave a message for people looking at me and say that she did it so I can do it too.

Right now I’m intimidated by people who have been successful. The people who went to Stanford or they went to these amazing places that gave them the edge and I had to buy my way into that by working hard, supporting myself on my own, having no network, and no guidance. My parents didn’t go these routes and we don’t come from wealth. So, it’s very much of a challenge.

But I also know my limitations. If I’m going to do something, I also know that I need to lay the fundamentals for it. I didn’t just start a company right off the bat because I needed some savings to feel safe. I worked for 10 years in the corporate world before I went to start a company. But when I did do all this, I just felt safe. Even if I fail, I have a fallback of my savings and I knew I would do it for two or three years and I had an exit strategy, which is when I reach so and so milestone and if I’m not at so and so stage, I’m gonna quit, I’m gonna swallow my ego.

So, you have to go in with all that, mindset-wise. That’s what I did. Some people go for years and years and I think the brick wall perspective is not that great for that scenario. Don’t be so stubborn that you think you are gonna succeed six years in just because you keep going. Gain some other experience that people are telling you that you need, before you go about doing this.

Shubha Chakravarthy: Have there been points where you’ve really been challenged to say, “This is a really dark moment” and if so, either technically or externally or internally, what has helped you get through them other than being the brick wall breaker?

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: There have been many dark moments. You question yourself when you walk out of a meeting. When you are a brick wall person you think that you would just do whatever it takes. It works negatively too. You go to a meeting, sometimes for a drink and you go on a weekend meeting or whatever and as a single woman, you never know while walking out, “Was it a meeting? Is that a successful meeting in the end or was it someone hitting on you?”

There were so many inappropriate things and you walk out saying , “Is it me? Am I worth this? Am I heading in the right direction?”

So, I started wearing a fake ring because I just knew it was in that direction. That didn’t stop many people anyway, so many dark moments around that but then there’s something there that happens that gives you a glimmer of hope, or you try to ignore that and you find another hobby.

There are two things that are clear in my mind — swimming and cooking, all cliché things sometimes as well. “You’re a woman and you cook, right?” That also works negatively in the sense that I don’t watch sports so there’s really nothing that makes me cool enough to be a part of the networks.

Sometimes it makes me feel bad about myself and I’m like, “Oh, I wish I magically was into horse riding or some stupid thing like that.” Nothing against people who like that but it’s like, “I didn’t have those networks all my life. I was just working hard to make it to the next day. I didn’t have time to pick up golf. I didn’t have time to learn about the best wines.”

So, I focus again and go back to clearing my head and figuring out, “Is this something I still wanna pursue? Is this gonna keep making me feel bad or do I need to do something else before I come back to it?” Those are the decisions you always have to make on your own strength. Again, brick wall doesn’t mean you walk all over yourself.

Shubha Chakravarthy: What have been some of the high moments, either personally or professionally?

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: I know I’m one of those people that don’t celebrate high moments enough, even though I know I need to. But I guess one of those things — the fact that I didn’t know how to get into college 20 plus years ago, didn’t even know who would accept me without SAT scores and such but then I applied to business school without knowing anything people prepped for like GMATs and stuff for long. But I applied to anyway and got on a wait list and found my way into college again.

Then 10 years later I got awarded the “Distinguished Young Alumni Award” from that school, from Chicago Booth last year, in 2021. Again, maybe it is not a big deal for many people, but it was a personal milestone. They give that award to one person every year and the people who won the year before me and after me are even more amazing.

I think personal milestones and things like that matter. Maybe a venture doesn’t mean anything but if it’s a thing from Stanford, maybe people care about it because that’s where a lot of VCs and startups come out of, not that Chicago is not a good school, it is one of the best schools for many other things. So yes, it matters for me and that was one of those things.

I didn’t tear up because at this point I’m so numb to some of those things like, “Oh, finally, the world’s recognizing all this but it is a moment to celebrate.” So, things like that matter. Things like — right now I’m able to fund many founders from the fund, but also personally I’m an LP in a few funds. A couple of those things matter to me since at one point I didn’t have a penny in my bank.

Shubha Chakravarthy: What is your vision for the future? What is the thing that takes your breath away and that you want to accomplish someday?

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: I’m still young and I’m still learning. My mission changes every day but for now it is simply to see how far I can go with this. Hopefully, I want to have a few IPOs under my belt and really make it a name in people recognize.

The mission here is that since I didn’t have the proper pattern that people would want, what are some other things you need to look for in a human, which I am also evaluating, like, “How do I recognize myself to fund someone like me so that they’ll be successful 10 years later?”

So, looking for that and hopefully getting some IPOs to really close that loop. I’m successful, but not that successful yet.

Shubha Chakravarthy: I think you are very successful. Have you found the code to finding the next Shruti? I’m curious.

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: Well, that would mean that they have to IPO before that and it is a great success and they are raising great capital and we have many founders like that. But unless the IPO, it is a very black and white business, and unless you make money and the money is very transparent, then you made money or you didn’t make money. It’s not like I made money in a secret world.

So similarly, my track record is also public. So unless any of these founders go public, then they haven’t broken out yet. We have unicorns, but we haven’t gone public.

Shubha Chakravarthy: Well, we’re rooting for the day when you will go public. What would you tell the youngest Shruti, if you were starting over? What would you tell her in terms of anything she should do differently?

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: It’s so hard because I’m here because of that Shruti. I hate those regrets but I always wonder, “What if I had moved to the Bay Area sooner? Maybe, but I don’t know since there’s always the other side. Maybe I would’ve been like the small fish in a big pond at that time.”

Why I’m here is because I was a big fish in a small pond and that way it is easier to stand out. It gives you confidence. So, I don’t know, I think I’ve done a good job of following my conviction but maybe I should’ve listened to myself more.

Shubha Chakravarthy: Any advice for other starting women entrepreneurs?

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: I don’t give advice. As I told you, advice comes from a place of your experience and sometimes when you ask people for advice, they have a different experience and a different life story. It’s not helpful to get advice from someone who didn’t go through your journey.

It is good to get feedback and 2 cents from people, but you have to make your own decisions from your journey. I don’t give people advice because I want them to listen to my message and listen to what I’ve done and take something away from it.

“Don’t listen to people”, is my real advice.

Shubha Chakravarthy: That’s great advice. Thank you for that, I’ll have to think about whether I should listen to it or not. Just kidding!

Shruti Van Dyke Gandhi: Yeah, it’s true!

Shubha Chakravarthy: Thank you very much, Shruti. This was a fantastic conversation and I’ve learned a ton and I’m sure others will as well. I’m sure you’ll be super successful and we’ll all be rooting for it. Thank you very much!