The startup was building a transformational hard-tech product. The technology was impressive. They had a functioning prototype, and a deeply experienced team. This should be a slam dunk, I thought.

But the problems started the moment I opened the pitch deck. Their market opportunity sizing didn’t target the problem they highlighted. Their solution didn’t tackle the problem head on. The product they were selling didn’t seem to address what their customers wanted. There was only an aura of massive opportunity around the idea – the details didn’t line up.

As I started digging into their files, I was surprised to see reams of data on customer problems, buyer economics, technical specs, and almost every other issue I might want to see in a startup asking for money. But there wasn’t a whisper of all this work in the story they told in the pitch deck.

The founders had tumbled into one of the most common pitfalls facing startups:

The last mile trap.

Here’s how this trap plays out: founders diligently do the customer and problem discovery work, and document all their findings in stacks of folders. They dutifully fill in the business model canvas or whatever framework they’re using.

Then they get stuck.

They can’t seem to make the leap from their findings to a compelling story that is appetizing to investors. It’s like they have all the ingredients for an amazing dish but no idea of how to put it together.

The Three Hidden Pitfalls

I’ve worked with dozens of founders, and I see three reasons why they routinely fall into this trap.

Framework Fixation:

Many startup programs use standard frameworks like the business model canvas to help founders build their startup idea. These frameworks are incredibly valuable early on in helping first time founders especially if they have no business experience. They break down the problem and make it actionable in small pieces.

The problem starts when founders fixate on these frameworks well past their useful life. You have to let go of the frameworks and adopt more relevant mental models as you go out into the market. When founders fail to do that, they are unable to prove to hard-headed investors that they have a fundable startup.

Shifting Standards

With canvas in hand, founders prepare pitch decks and start investor conversations. Equally competent investors can have a range of valid views about your startup, and many times they clash with each other.

When founders start to hear contradictory views from perfectly legitimate investors on everything from the customer segments they should pursue to their pricing strategy, they get paralyzed by doubt and indecision.

Precious time ticks by but they can’t decide or worse, they flip-flop – they don’t know how to make that call. They try to incorporate all views and end up satisfying no one single investor all the way to getting the check.

The Birds in the Bush Problem

Founders are visionaries: they clearly see the possibilities of a vastly better world. But there are dozens of ways to make this happen: multiple use cases, customer segments, product formats, revenue models, ways to go to market. The founder wants to do it all and do it right now.

Investors see the problem – it’s almost impossible to pull off more than one big idea at a time. They want founders to commit to one path that they can prove with high odds of success. This early success will give the founder the resources to tap new markets, launch new products and grow.

But founders are incredibly reluctant to commit to one market, one problem, one product as if by doing so they’re walking away from all the other opportunities for their amazing solution.

The result is a spaghetti pitch: no clarity on what the investor can expect the founder to do in the foreseeable future to make their vision a reality. Not a winning gambit.

A Simpler Way to Cover The Last Mile

There’s a much simpler and more powerful way to help you stay on track, pressure-test your story, and even make important decisions on your startup strategy. It’ll also arm you with the confidence to stand firm under intense investor grilling, or reconsider your path if there’s a compelling reason to change.

It’s a foolproof process that keeps you focused, clarifies decisions, and supports you with specificity and objectivity as you progress through the whirlwind of building your startup. Most importantly, it helps you self-correct early and quickly – a critical need as you move through multiple iterations of your market, product, revenue model and go-to-market strategy.

With this lightweight process in place, you’ll have the confidence to articulate to yourself or anyone else:

- Exactly how you’re planning to build your startup

- Why you made the choices you did

- What makes you the horse to bet on to win in this market

Best of all, it won’t add yet another burdensome task to your already overflowing plate. All you need is to add one more element to something you’re already doing: building your pitch deck

The One Step That Makes All The Difference

Today your startup’s strategy is probably scattered across multiple slides in multiple versions of the pitch deck, files and data sources. Bring order and sanity to this process by creating a single spreadsheet to summarize your story.

On this sheet, create a row for every critical element of your pitch deck, in this order:

- Problem

- Solution

- Market

- Product, including proof of effectiveness or benefits

- Beachhead customer

- Monetization and revenue model

- Go-to-market / channel strategy

- Margin and profitability

- Competitive advantage (including IP etc)

- Team

- Execution roadmap

- Fundraising ask

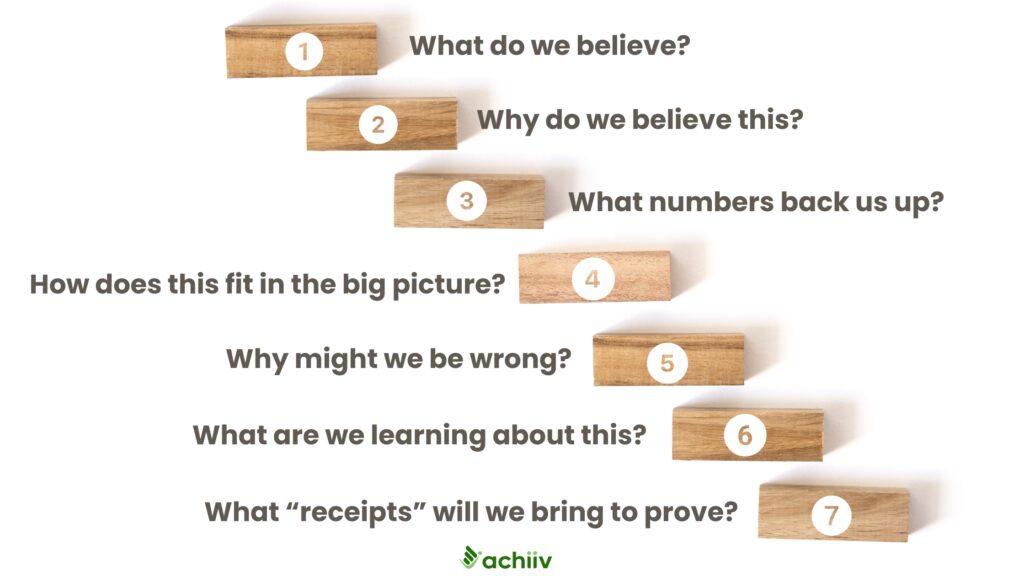

Add columns for each of the following:

- Current thinking: What is our current hypothesis on this specific item?

- Rationale : Why do we think so? How credible is reasoning? What data is there to back our hypothesis?

- Quantification and metrics: What are the quantifiable points of our answer? (any numbers to add specificity to your answer).

- Alignment: How does this choice work with the big three: problem | market | product ?

- Pushback and defense: What can go wrong with this? What are the weak points? How would we counter them?

- Notes and comments: Brief notes on any comments / questions / insights through your startup building process.

- Links to sources: Attach files, URLs, or other documents you need to support your main storyline

Let’s say you’re building a startup that provides AI-enabled software to balance energy consumption for real estate. Here’s how you might work through this exercise for your monetization and revenue model:

- Current thinking:

- Flat maintenance fee per building per month

- Variable fee based on monthly energy consumption

- Rationale:

- Method saves 35% on energy costs on average for a commercial building with 25,000 sq ft of space.

- Expected gross margin is ~55% (link to the sheet showing your calculations and assumptions)

- Quantification and metrics:

- Flat fee: $500 per month per building;

- Variable fee of $2.50 per kwh consumed

- Alignment:

- Property management companies already spend $x per square foot to solve this problem

- Pushback and defense:

- A concern is that our price point is too high.

- We will rebut this by showing that the total cost of operation for the property management company is lower by more than 30%

- Notes and comments:

- Highlight quotes from property managers about your attractive price point

Taking a few hours to do this simple exercise provides enormous clarity, eliminates mental clutter, and shines a huge spotlight on where you have big gaps. And it’s always there – you don’t need to carry it around in your head.

Your to-do list is automatically prioritized because you have to tackle the upstream items first before you fix the downstream items.

Give Yourself the Gift of Confidence and Clarity

Building startups is hard, thankless, backbreaking work. Give yourself the gift of confidence. And your team, your advisors and mentors, the gift of clarity. Focus on first things first, do the vital few that will have a disproportionate impact on your success and progress. And have receipts ready to show for every part of your story.

Are you ready to leap tall across that last mile?