I was recently chatting with a founder who’s developing a technology to decarbonize heavy manufacturing. As we discussed his fundraising challenges, he made an offhand comment wishing he had more options than “just grants and VC” because the time horizon and capital intensity of hard tech scale ups are so different.

That led to a whole new conversation on creative funding strategies that are uniquely fitted to hard tech but are little known and even less documented in the startup universe.

To start bridging that gap for deep tech and hard tech founders, I decided to write this post outlining the basics of non-VC focused funding strategies.

Important disclaimer: These ideas are discussed for information purposes only. Please consult qualified, licensed professionals to get advice tailored to your specific situation.

Why a New Funding Playbook?

Fundraising for deep tech is very different from “regular” startup fundraising. For example, the “valley of death” your startup faces looks different – you must prove your technology, usually via a pilot, before you can attract serious money, but you need that capital precisely to fund the pilot! You also need many times the capital that a “typical” startup might need, with much longer timelines and greater adoption risk because there are other early stage technologies racing to solve the same problem for buyers. All told, this is a long game fraught with risk but promising potentially very big rewards.

VC’s, however, want rapid, high-multiple returns and tend to like business models that scale and exit quickly. So relying solely on VC’s might be a tough game at this stage. Grant funding from government and related agencies has been another mainstay. But many deep tech startups especially in life sciences have seen that evaporate.

The Job to Be Done

To start with, it helps to go back and ask what the “job to be done” is for the capital you’re currently seeking. In deep tech, you need capital to do one of five different jobs:

Job #1: Technology Risk Reduction

Prove the product works at a higher scale (e.g. in a pilot plant) than previously established (e.g. in the lab). The biggest expenses are scientific and engineering talent, prototyping, building plants and equipment, lab testing or field trials. The risk here is that the technology fails at the higher scale, eliminating the entire reason for your startup.

Job #2: Infrastructure Access

You may need money to purchase access to specialized tools, or facilities (e.g., test benches, pilot lines, cleanrooms). The risk is lower if the product functionality is already proven, so market demand then becomes the biggest risk.

Job #3: Working Capital or Runway Extension

You might also need money to pay salaries, rent or other “regular” expenses that aren’t explicitly tied to a milestone or valuation event. Or you may have run out of money before you hit your next milestone target. This happens because founders typically underestimate time and costs, and overestimate traction and demand. It also happens because of exceptionally long lead times for equipment, parts, permits, etc. So there is plain-vanilla repayment risk that’s dependent on both product efficacy and strength of demand.

Job #4: Product Customization and Market Readiness

Even after proving the technology works, you may need to customize it, produce pilot units or demonstrate production pre-sale before a large customer will commit to a contract. Your risk is lower if many customers have similar requirements. A second job in getting the product ready for commercial sale is obtaining legislative support – government relations is an expensive line item, and often indispensable.

Job #5: Scaling and Growth:

With a proven product and market demand, you’ll need capital to build integration into partner or customer infrastructure, scaling up manufacture or enter new markets. This is usually a later step once the technology and demand are proven.

What’s the job you want your next raise to do?

Matching Capital to Task

With a strong grasp of the job to be done, you can now assess your options. The goal is to generate multiple options for each job. Here are a few examples to consider:

#1: Technology Risk Reduction: Strategic Pilot Funding (Government or Corporate)

In 2023, Zap Energy, a fusion startup, received $5 million in non-dilutive funding from the U.S. Department of Energy under the Milestone-Based Fusion Development Program. The goal was solely to design a pilot fusion plant before the technology was market-ready.

This type of strategic pilot funding may be a viable source to reduce technology risk if there are active, well-funded public programs like those from the Department of Energy, The National Science Foundation and DARPA that have traditionally supported technology commercialization. It helps if your tech aligns with a national priority, a specific focus technology or industry pain point (e.g. energy resilience, defense, manufacturing).

#2: Infrastructure Access: Leasing or Buying Used

When you need to set up a plant or facilities, you can rent equipment instead of buying. Another creative option is to purchase heavily discounted used equipment that you can cheaply repurpose to meet your immediate needs. Elise Strobach at AeroShield, for example, avoided raising millions of dollars by buying used equipment she found at a fraction of the price.

This path works well if your use case involves standardized equipment, especially if there’s an existing aftermarket for buying and selling.

#3: Runway Extension: Buy-Back Equity or Redeemable Founders Shares

A buy-back agreement is an arrangement where a startup takes on an investor (often via equity or convertible instrument) and gives the founders an option to repurchase that equity in the future.

It’s a structured “exit” agreement where the investor provides funding now, and the founders buy back the shares later ( at a predetermined price). This lets founders treat the investment more like temporary equity – capital for now, ownership back later.

This works only if you can access flexible capital like angels or family offices that care more about capital preservation and/or your mission, and aren’t fixated purely on financial returns. Also, your milestones must be crystal clear and provide sufficient cash for you to actually execute the buy-back (e.g. a big contract) that aren’t reliant on a dilutive raise in the future.

#4: Market Readiness: Advance Purchasing Agreements

While paid pilots get funding commitment for a specific project, advance purchase agreements are more long-tailed, with funding provided in advance in exchange for early access, exclusive rights, favorable pricing and/or product customization.

For example, advance purchasing agreements (termed “advanced marketing contracts, or AMCs) were used to procure Covid 19 vaccines during the pandemic.

This tool works best if you’re targeting B2B buyers who have urgent, high-value problems and are used to innovation risk (e.g. aerospace, defense, manufacturing). Your technology has to be proven enough to make buyers comfortable paying upfront, with tight, credible IP and knowhow protection. It helps to have some objective external markers of trust like industry certifications or regulatory approvals.

Also, buying companies should be flexible enough to allow for early stage vendor engagement.

#5: Scaling and Growth: Joint Development Agreements (JDAs)

When your technology is proven and you need financial muscle to scale, Joint Development Agreements (JDA) can unlock capital, infrastructure, and credibility especially if you’re operating under a university license.

In a JDA, your startup contracts with a corporate, manufacturer, or research institution to co-develop a pilot, product, or prototype. Your incentive is the cash they contribute (in addition to in-kind resources like engineers or facilities). In return, you give them preferential access to your technology, product, pricing, etc. This is important because typical university licenses give you the flexibility to enter into these kinds of agreements, but may not allow you to sub-license your technology.

For example, Cemvita, a Houston-based synthetic biology startup, partnered with Oxy Low Carbon Ventures to co-develop a pilot bio-ethylene plant. The plant was jointly funded, designed, and validated as a shared R&D effort.

Consider this source when you need facilities or specialized talent, like engineers. Also ensure your IP is rock-solid and auditable, and your partner is credible and can be trusted to deliver.

Taking Action

Now that you have a better sense of what jobs different sources of capital can do, you can take control by building a custom-fit funding plan for your needs:

- Clarify the specific job your next funding needs to do. What exact problem or problems are you looking to solve? Are there multiple jobs you need to complete in parallel? What are the objective markers of successful performance?

- Get granular on the exact resources needed to get that job done – do you understand both the cash and “in-kind” version of each of these resources? High level estimates won’t get you the insights (or resources) you need.

- Identify multiple potential sources both at the level of the entire ask (e.g. raise amount), as well as the individual elements (e.g., equipment). What additional avenues and options do you see? Can you access new funding sources because you need less money? (e.g. angels may now become a viable option)

- Prioritize beginning with the easiest avenues especially if they don’t need upfront cash. If these resources can reduce risk and demonstrate increased traction, all the better.

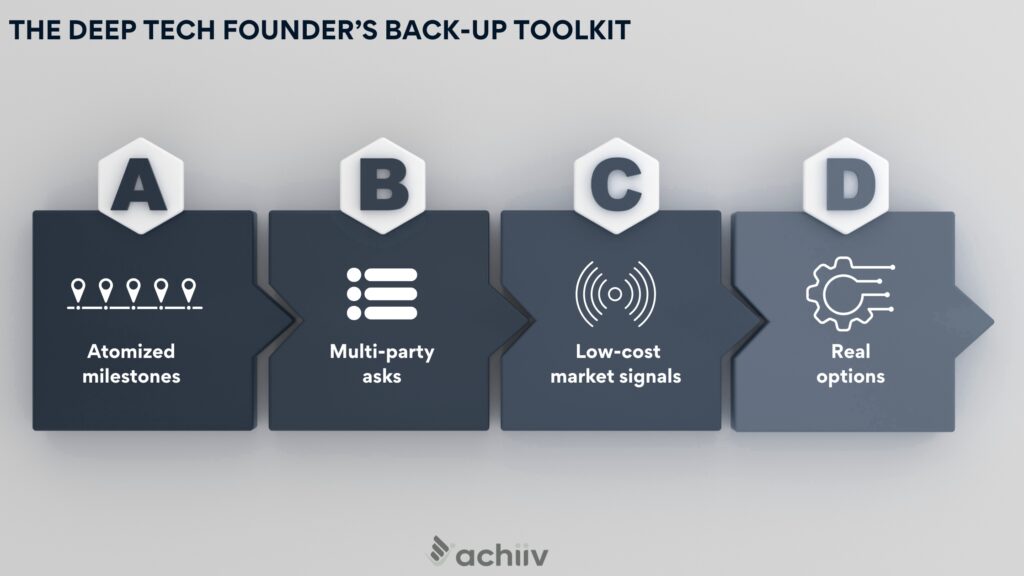

Still stuck? Here are absolute worst case options to consider:

- Break down milestones into micro-chunks. For example, can you turn a $2 million pilot into a $200k bench trial with a willing partner with an urgent need?

- Pitch components of the milestone to mission-oriented organizations. For example, are there grants or vouchers available to locate a lab in a specific area?

- Focus on achieving progress via market signals that don’t require capital, for example, LOIs, regulatory pathway conversations, advisory board commitments from industry partners.

- Explore option-creating activities (e.g., funded fellowships, paid consulting, business and relationship building)

Where are your hidden opportunities? What actions will open up new pathways and buy you more time? What one thing will you do now to give your startup a better shot?