In 2007, I was working in the subprime mortgage industry, and on the surface the housing market looked unstoppable. Homeownership was at record highs, lenders were booking profits, and the system seemed to be thriving.

But the first cracks appeared deep in the math of the loan portfolios. On paper, the loans looked fine, but foundational assumptions holding up these portfolios were cracking at the seams. Once these critical fault lines split, like how many loans went bad, the collapse was inevitable.

This “deep math” issue is just as relevant with startups, and is just as frequently missed by founders. They usually think they’re not getting funded because they lack traction or haven’t brought the product along far enough. So they spend nearly all their time polishing the pitch and almost no time thinking through the deal itself.

But they fail to raise because of foundational math flaws hidden deep in the pitch.

Founders consider items like the capital plan and deal structure to be “boring details”, so they give them very cursory, high level treatment.

But to investors, these are first-look factors that make or break their interest in the deal. To understand why, let’s step into their lived reality for a second. When an investor sees your pitch, their first question is about the mechanics of how they’ll get money back if they put it into your startup now. If that doesn’t work, everything else about your startup is irrelevant.

These “footnote” factors for founders, stuff like cap tables, exit math, dilution, and capital strategy, drive the two biggest factors for investors – the returns they expect to get and the price they pay for that right. If these don’t work, there is no conversation, no matter how great your startup is on its own.

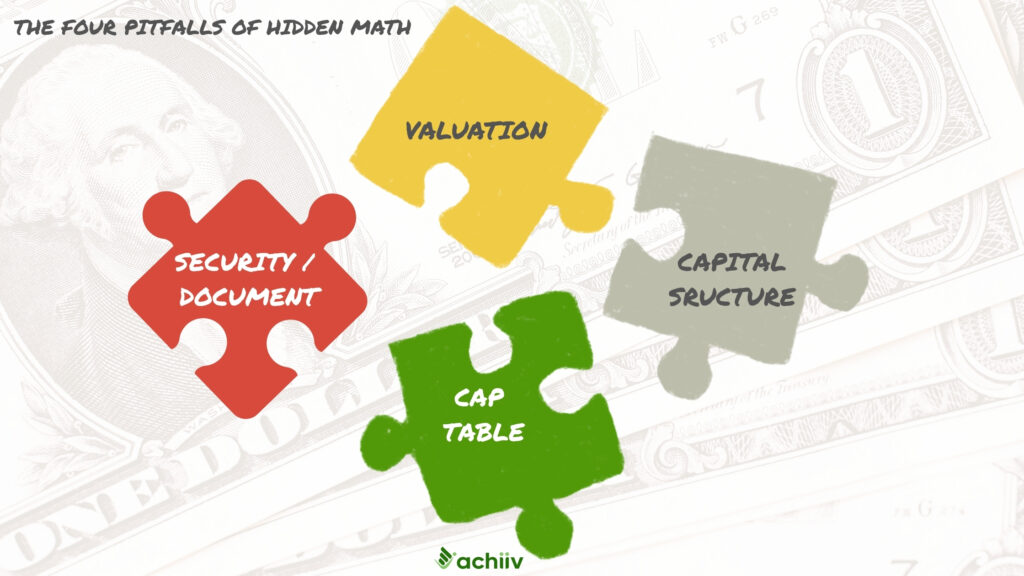

Four Pitfalls To Watch For

As was the case with the 2008 crash, it’s rarely the story on the surface that breaks you. It’s the math underneath. Here are the four places founders get it wrong most often.

#1 | Valuation: When the Numbers Don’t Add Up

Valuation is the number founders fixate on most. In my conversations, investors tell me it’s also the one most likely to quietly kill their deal. This error happens most frequently with first-time founders doing their first outside raise:

- Valuation is too high: Typically this is because founders are using unrealistic comparables from a completely different market climate (e.g., pre 2022), or because they have an unrealistic sense of what their startup is worth (the “beautiful baby” syndrome). When valuations are too high, investors suspect you’re financially naïve (not a good look. The other reason is that they can’t make money because there’s not enough room for the valuation to grow for them to make their target return

- Valuation is too low: On the flip side, if your valuation is too low, you’re setting yourself up for so much dilution that soon you won’t have any incentive to work hard towards that exciting exit.

- Founders have tunnel vision: Many founders fixate too much on this one number, refusing to budge, while ignoring other important terms such as liquidation preference, which could have bigger impacts on exit outcomes. When investors see this, they know they’re not dealing with a financially astute founder.

As one investor said:

”It’s not the number—it’s whether it makes sense in the bigger picture. If you’re raising $4 million at a $20 million pre-money with no revenue, how do you get to a 10x outcome?”

#2 | Capital Strategy: Failures Waiting to Happen

If valuation is the number founders obsess over, capital strategy is the one they almost always overlook. Too many founders walk into a raise thinking only about the next 12–18 months, confident that if they nail this story right, the rest will fall into place.

An investor, on the other hand, has zoomed out already, and is asking herself:

- How many rounds will this company need?

- What does that do to my ownership?

- How much will my share get “crammed down”?

- What size exit would it take to make the math work after multiple raises?

- What are the chances of that happening, for this founder in this sector and in this market?

- Do I still want to make this bet?

Investors are very leery of founders who lack basic capital fluency. As one investor put it:

“They’ll say, ‘We’re going to exit at $100 million, so your 10% will be worth $10 million.’ But that 10% is really 3% after Series B.”

#3 | Cap Tables: Ownership That Collapses Under Pressure

To many first time founders, a cap table is a nasty spreadsheet that they will do anything to avoid looking at until it becomes completely unavoidable. To add to that, they also take steps in a piecemeal, unthinking way that really damages the big picture of their startup’s ownership:

- They hand out equity too freely to friends, advisors, or small checks, without stepping back to look at what it will do to them in the long term

- They raise money on multiple small SAFE or note rounds, each with different terms. These stacked SAFE’s wreak havoc when trying to put together a coherent picture of true equity ownership

- Many first-time founders feel grateful for any investor interest, so they over-concede equity instead of holding their ground in the early rounds.

By the time they reach institutional investors, founders may already be sitting on too little equity to stay motivated through the years it takes to exit.

But that’s not all. A messy and overly cluttered cap table makes future decisions a nightmare -often, early investors can’t even be contacted to get approval for decisions that require majority votes etc.

A messy cap table is a total no-no to serious investors. Here’s what one said:

“The founder has 30%, three angels have 25% combined, and the rest is split between advisors and convertible notes. I’m out.”

#4 | SAFEs: Short-Term Fixes That Compound Long-Term Risk

For many first-time founders, the choice of investment instrument feels like a technicality. SAFEs, in particular, are appealing because they’re quick, cheap, and easy to execute because they don’t require a lot of lawyers’ fees to get done.

Where it goes awry is when founders start to raise multiple stacked SAFEs, each with its own cap and discount rate. It gets worse when they contain “most favored nation” treatment or other non-standard clauses that distort ownership beyond recognition.

It’s a rare founder who tracks these carefully, even if they could logically be able to do so. So when they start raising their first institutional round, their cap table looks like a mangled mess that no sane investor wants to touch.

Investors could not be more clear:

“The founder had four SAFEs outstanding. Different terms. Different discounts. I spent two hours trying to unwind it and finally said: Pass.”

“If I’m going to lead a priced round and clean up a rat’s nest of SAFEs, that better come with a big discount. Otherwise I’ll move on.”

Closing the Gap

Among the dozens of founders I have talked to at length, I haven’t seen a single one who missed these details knowing the consequences. It’s because one or more of these factors were at play:

- Founders attend accelerators, but few teach them the fund mechanics or return math that are so important to investors

- Many founders get swept up in starry-eyed unicorn stories where vision alone carries the day and that that’s all they need to “live happily ever after”

- In solving pressing and urgent “today” and “yesterday” problems, deal-related issues seem vague and okay to postpone, until it’s too late

And worst of all, when they finally come face-to-face with the consequences of these omissions, few investors will care to stop and explain what’s really killing the deal. It’s much easier to give euphemistic responses like “It’s too early” or “You don’t have traction”, rather than to sit the founder down and explain the hard facts of investor math.

But you always have the ability to take control now:

- First, sketch out your capital roadmap at least high-level. For your startup to succeed (exit or cash breakeven), how much money will you really need, and when? How do those needs line up to conventional fundraising benchmarks in today’s market?

- Master your cap table. Do the work of understanding fully-diluted ownership even on a spreadsheet. You may not master it in one day, but you’ll be infinitely better off than you were flying blind.

- If you’re planning to raise soon, take a good, hard look at the tradeoffs between multiple “easy” steps today (e.g., stacked SAFE’s) and the long term cost and consequences for your ability to raise all the money you’ll need.

What’s the single most impactful capital related step you will take next?